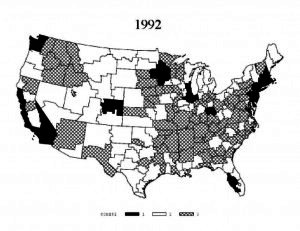

For 1992, there are 15 regions in the upper cone, 84 in the middle and 82 in the lowest cone. Figure 13 maps the three cones for 1992. Again black and cross-hatching indicate significantly higher and significantly lower relative wagebills respectively.

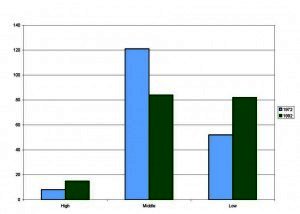

There is a large amount of movement between cones over the period with most movers leaving the middle cone as shown in Figure 14. 19 regions moved to a higher relative wagebill cone and 42 regions moved to a lower relative wagebill cone. This movement over time to the extreme factor price cones is somewhat surprising given the usual assumption that regions in the US are becoming more integrated and thus more likely to face the same relative factor prices. However, the distribution of regions across cones does not tell us whether factor prices are moving farther apart. The cones themselves could be moving closer together even as regions become more evenly distributed across cones.

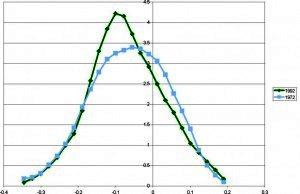

To check this, we look at the distribution of coefficients from our regressions with the US as the base. Figure 15 shows the histogram of coefficients for 1972 and 1992. While regions were separating into cones, the overall dispersion of relative wagebills did narrow slightly during the period, as we would expect if the US were becoming more integrated. However, the reduction was not sufficient to suggest that relative wages were substantially more equal across regions. To examine what was happening to the cones themselves, we report the means and standard deviations of the estimated coefficients by cone in Figure 16. While cones were becoming more similar in terms in relative wages, the within cone distributions were tightening.

From the coefficients using the US as a base, we can ask whether the average pair of regions has a larger or smaller difference in relative wagebills in 1972 and 1992. The distance between regions as measured by the significance of the wagebill rejections is increasing, however, the average distance between regions based on the regression coefficients is decreasing from 0.121 to 0.109. Comparing the average distance between pairs of regions in the high and low cones, we find that it decreased from 0.302 in 1972 to 0.260 in 1992.

The results in this section provide strong evidence against the hypothesis that all regions in the US face identical relative factor prices. In addition, while a number of regions have moved across factor price cones, there remain at least three distinct relative factor price cones even in 1992. In the next section, we explore another dimension of the HO model and ask whether the differences in factor prices are correlated with industry mix in the regions.

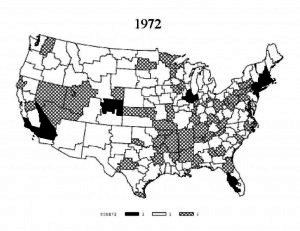

Figure 12: Labor Market Areas and Cones – 1972

Figure 13: Labor Market Areas and Cones – 1992

Figure 14: Distribution of Regions across Cones

Figure 15: Relative Wagebill Density across Regions

Figure 16: Estimated Coefficients by Cone (US=base)